Evidence-based Insights on Remote Work and Productivity

The Covid-19 pandemic proved to be a watershed moment for the world of work globally, from which there is no going back. According to some of the most recent research reported from the US, remote work remains prevalent, with a survey finding that it currently accounts for over a quarter of paid full-time workdays.

In this new normal, a fundamental unresolved question is the impact of remote work on productivity. Various research studies carried out during the pandemic, and since, have yielded conflicting results. For instance, in a 2021 study by Owl Labs, 90% of surveyed employees said they were as productive or more working remotely, compared to working in the office. Other studies have shown that remote work can hamper productivity, due to feelings of isolation and higher stress.

A key problem with most research on the subject is that it focuses on self-reported and subjective responses, which can vary depending on whom the question is being posed to. To try and get a clearer picture, we analysed the most recent macroeconomic data and firm-level research on labour productivity, to arrive at a more evidence-based understanding.

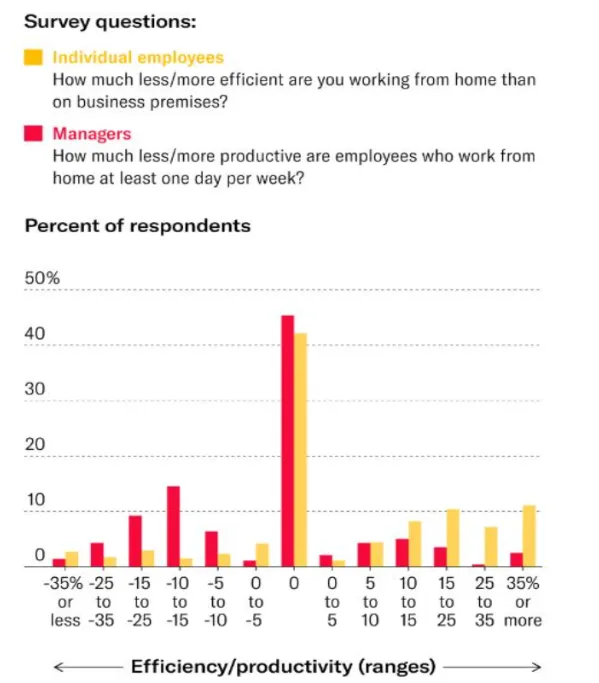

Findings on the link between remote work and productivity seem muddled because they rely on two stakeholders with very different views. In fact, managers and employees have almost diametrically opposing views on this subject, according to recent research appearing in the Harvard Business Review.

It shows that close to half of all managers and employees think that there is no significant impact of remote work on productivity, either way. But of the remaining half, opinions are sharply divided. In this sub-set, most managers seem to think that remote work has a negative impact on productivity, while most employees believe that it has a positive effect on their output.

To investigate this fundamental disconnect within companies on the question of remote work’s impact, we decided to look at what the actual data is saying at the level of national economies. By doing so, we were able to go beyond the firm level and assess what the broader impact has been.

To do this, we reviewed labour productivity data for two major economies prior to and during the Covid-19 pandemic (when remote work suddenly became the norm) to identify what, if any, change in the historical pattern has taken place. First, we assessed data from the US, the world’s biggest economy with a large services sector. We then looked at the same type of data for Australia, a key economy in Asia Pacific with a relatively large agriculture and extractives sector, to see if its different composition (compared to the US) had an impact on the productivity-remote work link.

The simple economic measure we tracked in each country was an annual labour productivity index, where labour productivity is defined as the real economic output divided by the total number of hours worked in a given period. This gives us an estimate of how productive the overall economy, or certain sectors within it, has been over time.

United States

In the US, we analysed the latest data published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, covering various aspects of labour productivity. We specifically looked at the historical pattern of labour productivity across major economic sectors, up to 2021.

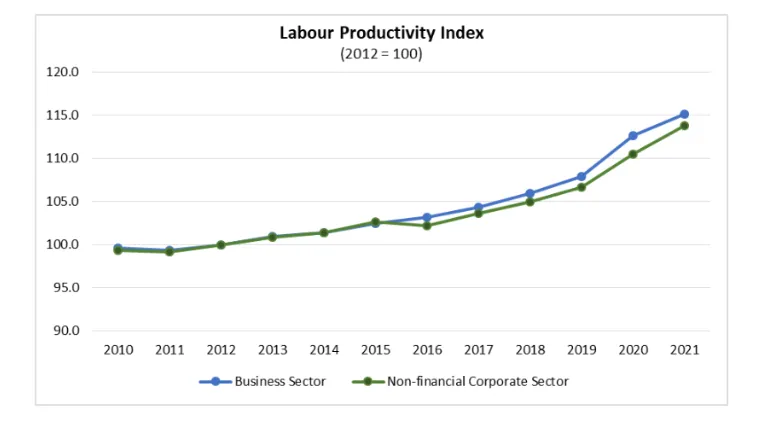

First, we assessed two sectors where remote work was most likely to have been adopted quickly, after the pandemic began in early 2020: the business sector and the non-financial corporate sector.

The data show that labour productivity in both these sectors had been increasing at a steady rate during the decade leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic.

A clear implication is that as the large scale transition to remote work took place during 2020-21, not only did labour productivity not decline, it actually increased at a rate much faster than its historical growth rate.

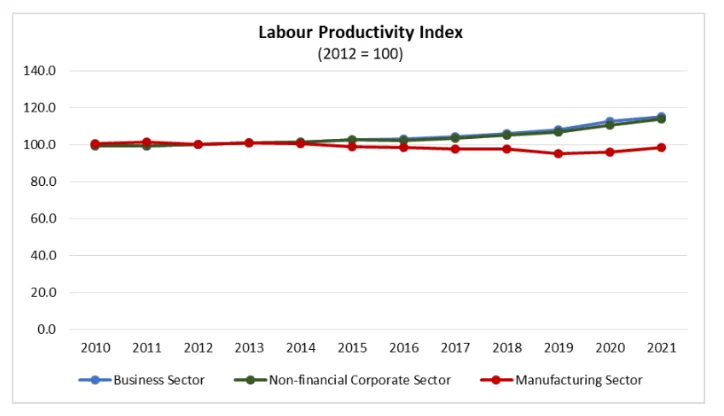

To further test this, and see whether the productivity boost in the US labour force could really have been caused largely by remote work, we added a third economic sector for comparison: manufacturing. Because jobs in manufacturing were less likely to have been done remotely, we should expect to see a much smaller rate of increase.

And that is exactly what we observe. Labour productivity in manufacturing remained stagnant during 2010-19, barely growing at an annual average rate of 0.1%. In 2020 and 2021, it grew at 0.9% and 2.5%. As Figure 2 shows, labour productivity in manufacturing picked up during the pandemic, but at a much smaller rate than in the other two sectors, staying around its historical average.

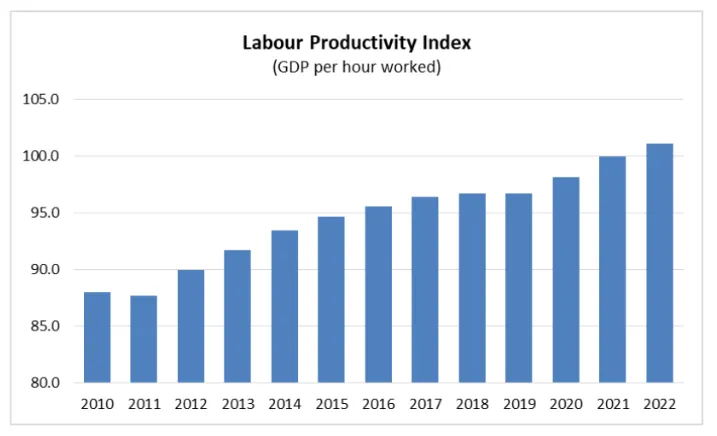

For Australia, we reviewed the latest available data published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Again, we analysed the historical pattern of labour productivity, but this time for the economy as a whole (due to the reporting structure) instead of different sectors within it.

In Australia, the situation seems very similar to that of the US, with the remote work-related productivity boost even more apparent.

The first insight is that like in the US, the rate of growth in Australian labour productivity was higher after remote work became widespread compared to its average in the preceding decade, although the difference is not as pronounced as it is in the US.

The second unique aspect of the Australian case is that in the three years prior to Covid (2017-19), labour productivity was virtually stagnant, showing marginal average annual growth of 0.4%. In the three post-Covid years of remote work (2020-22), the average was 1.5% - more than three-and-a-half times higher.

This brief analysis is based on macroeconomic data from only two (albeit large and dynamic) countries, and is hence limited in nature, so extrapolating its results to the firm level or the wider global economy has to be done cautiously. Nevertheless, some insights and further questions for exploration do emerge.

It can be safely concluded that the shift to remote work has not harmed overall labour productivity. The data show that it continued to increase after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, more or less in line with the historical trend. One of the possible reasons for this was that in more developed economies, most economic sectors - such as services - were easily able to have employees shift and adapt to remote work. This probably avoided any major disruption to output, and hence to labour productivity.

National level data indicate that labour productivity has maintained its upward historical trend, or received a boost during and since the pandemic. However, at the firm level, things are much less clear. The reason is that at the micro level, productivity is likely to be more sensitive to various factors, such as:

A recent study published by the University of Chicago analysed data from an Indian IT firm with over 10,000 skilled workers. Its results are highly relevant as the occupation under study was amenable to remote work, and involved significant cognitive, collaborative, and innovation tasks.

Among other findings, the researchers noted that some aspects of work could be more difficult, or take longer, to perform in a virtual environment. In particular, while working remotely:

The assessment of the impact of remote work on productivity will require ongoing research, covering more economies and industries. Nevertheless, our brief analysis points to some trends that can be discerned reasonably confidently. We can be fairly sure that at the economy-wide scale, workers collectively are at least as productive, if not more, since the transition to remote work occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic. This should give companies confidence, but they should also watch out for potential productivity-sapping pitfalls of remote work we have identified in this article. Therefore, firms will need to proactively design strategies, tools, and training policies to make the most of remote work, while helping employees deal with aspects that can lower efficiency.